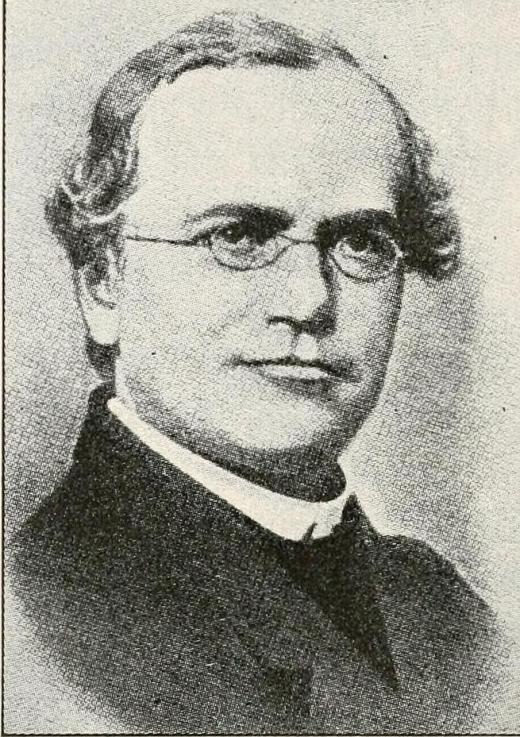

Hybrid maize, also known as hybrid corn, is an agricultural product created by cross pollinating different inbred lines of maize. It accounts for more than 90% of all maize grown in the United States due to its large size and uniform appearance. The processes used to interbreed plants were first understood and documented by Gregor Mendel in the 1860s, but were not widely applied to agriculture until the 1930s.

Prior to the discovery of hybrid maize, traditional maize breeding was very simplistic. Farmers would select a group of maize plants that shared a desirable characteristic, such as disease resistance, large size, height, rapid growth, or appearance, and then try to amplify those traits by planting those plants together and allowing them to breed. Accidental pollination was very common, so the initial plants in the group were not always only the ones that farmers had selected. Over the course of several generations of inbreeding, this group of plants would become a strain, sharing similar genetic makeup as well as physical traits.

In 1908, a researcher discovered that if he took two inbred strains and interbred them, the resulting hybrid maize was a much larger and hardier plant than either of the inbred lines had ever produced. The agricultural implications were staggering, and farmers could suddenly produce much more corn than they had been able to produce before. Later, another researcher improved the process of interbreeding by suggesting that two hybrids could further be crossbred to produce a plant with high production and a high percentage of viable seeds. This type of hybrid became known as a four way cross. Four way crosses were difficult to develop, however, because for any four inbred strains there were numerous possible ways to combine them, each of which had to be grown and compared to the others in order to select the most productive and viable.

The main disadvantage to growing hybrid maize would not be discovered until many years later, when farmers discovered that uniform appearance carried with it a dangerous genetic uniformity. The more effort farmers put into making sure that the plants all looked the same, the more genetically alike they made them. Double crossing the lines prevented many of the disadvantages created by traditional inbreeding, but it massively increased susceptibility to disease. Without genetic diversity to protect a crop of hybrid maize, a single pathogen could spread through a field, moving from plant to plant, infecting everything. Modern hybrid maize counters this problem by crossbreeding hybrid lines with open pollinated maize to produce varieties that have specific traits but maintain some degree of genetic diversity.